What did King Tut look like?

The History of Tutankhamun

Almost exactly 100 years ago, British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered a stairwell in the Valley of the Kings. The very next day, he followed the stairs, and was thrilled to find an undiscovered tomb, with its inner door still sealed – an extremely rare treasure.

In it was the Boy King Tutankhamun. A pharaoh who had reigned for only 10 years – the blink of an eye in historical context. It was a discovery for the ages, one that revealed thousands of perfectly preserved Egyptian antiquities and captured the public imagination.

Today we’ll talk about what we know of King Tut’s history, his mummy, and then of course reveal what he may have looked like.

King Tutankhamun was born in Egypt around 1341 B.C.E, during what’s called the New Kingdom period. This period introduced some of Egypt’s most famous Pharaohs, like Hatshepsut, Thutmose and Akhenaten.

Tut’s biological mother’s actual identity is unknown, but we do have her mummy. Genetic analysis shows she is likely the “Younger Lady” found in tomb KV55 – who was found to be the full sister of her husband, Akhenaten.

The only real reason for Tut’s notoriety is his tomb – before its discovery, Tutankhamun was barely a footnote in most Egyptian histories. We don’t actually know much about his reign. Ascending the throne around age 9, he would have been too young to truly rule. He likely relied heavily on his advisors.

The young King had inherited a country in turmoil – weak and fractured from the religious upheavals. This was Tut’s main agenda as King: Reversing his father’s radical religious reforms. As he ascended the throne, he changed his name officially from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun, removing the association to Aten, the Sun God. A carving found at Karnak indicates Tut’s unhappiness with his father’s reforms, stating “The Gods were ignoring this land” because of his father’s follies.

The goal was to provide stability to a fragmented Egypt. During his reign, he commissioned new statues and building projects, and also moved the capital of Egypt back to Thebes. He restored temples and sculpture-works that had been destroyed by Akhenaten. We know that Egypt saw war during his time as King – His tomb was found to contain armor and other military items, although it’s unclear if Tut himself used them.

Tut was married to his half sister, Ankhesenamun. The couple were unlucky, only having 2 daughters who both died stillborn, no doubt due to generations of inbreeding (family tree at bottom). His death marked the end of his royal line.

Tutankhamun died in 1323 B.C.E, around the age of 18 or 19, and was buried in an atypically small tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

Tomb Discovery

Three thousand years later, Howard Carter, under the patronage of British Lord Carnarvon, went looking for it. Carter had been excavating the Valley of the Kings for a few years when he set his sights on finding the boy-king’s tomb. He believed that there was at least one more undiscovered tomb in the valley, probably buried under piles of debris from other excavations.

Lord Carnarvon was growing impatient – he told Carter that 1922 would be the last season of funding he would receive.

But finally, in November, Carnarvon received an excited telegram from Howard Carter. “At last I’ve made a wonderful discovery in the Valley – a magnificent tomb with seals intact.” The tomb would become known as KV-62.

Tut’s tomb was found during what can only be described as the wild west of Egyptology. At this time, the British occupied Egypt but didn’t officially hold it. Unfortunately, the entire media storm and credit around the tomb’s discovery fully circumvented Egyptian Authorities. In fact, the Egyptian government seemed to have no say at all in the excavation. Carnarvon even signed an exclusive contract with the London Times, giving the paper exclusive rights to images from the tomb. There was some justice that in the end, the treasures went to the Egyptian museum, and not to the British or Metropolitan Museums as originally promised.

Some even thought the justice extended even further: Lord Carnarvon died mysteriously just four months after entering the tomb. Journalists in the 1920s were swift to capitalize on the “Curse of the Pharaohs”. They attributed over a dozen deaths to the curse, although later studies showed that most people who entered the tomb lived an average lifespan.

Later that same month, the team began their excavation. The riches they found were unimaginable. One specifically puzzled archaeologists: an iron dagger, made centuries before humans had even invented iron forging. It was found to have been forged from a meteorite that had fallen to Earth, no doubt a completely mystical object to the Ancient Egyptians.

Also found were 413 small-scale models of servants, meant to help him in the afterlife. A golden throne depicting Tut and his wife. A broken down chariot and other remnants of war. A scale model of the King, which some scholars believe to be a garment mannequin. There were also hundreds of other items found – jewelry, statuettes, clothing, and other riches.

Although these objects are magnificent, there is still a sense of historical removal. But inside the tomb are also a few utterly human, heartbreaking details. A wreath of flowers was found around the sarcophagus, which Carter said still retained their color after 3000 years. 2 tiny baby mummies, Tut’s two stillborn infant daughters, were placed near him. The tomb also contained his childhood toys, buried with him. Many of the items show ducks, an animal which he seems to have loved, which is also important to Egyptian society.

Unfortunately the mummy itself was very damaged. In fact, it was actually charred. It’s thought that a high amount of oil used on Tut’s body during burial actually combusted inside the tomb in antiquity, causing large amounts of damage before it was even opened.

In addition, Carter and his team were not gentle. They ended up basically chiseling the mummy out of the coffin, resulting in massive damage.

The trauma on the mummy, which we now know was sustained after death and burial, was what caused scholars at some points to believe Tut was brutally murdered. And many theories and mysteries still swirl around his mummy and burial.

It’s hotly debated whether or not Tut’s tomb was actually meant for him, since it appears to be hastily finished. Professor Ralph Mitchell analyzed some mysterious brown spots along the walls of the tomb, which he found to be microbes – bacteria that had grown when the tomb was sealed with wet paint still drying inside.

Some scholars believe the burial site and objects were originally meant for someone else – perhaps Nefertiti, his sister Meritaten, or another high ranking official.

Others believe that the unusually small tomb is just an antechamber, leading to more riches. However, more recent radar surveys suggest this is not the case.

How sick was Tut and how did he die?

We know Tutankhamun was significantly inbred, which no doubt led to some health issues. However, he may not have been as sickly as some re-creations suggest. There’s a lot of evidence indicating his death was surprising to his family, meaning he must have been in fairly good health beforehand. Many of his genetic maladies were found to be maybe nuisances in daily life, but not his actual cause of death.

A 2010 study confirmed much of what we know about Tut’s body and death. (Credit Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family by Zahi Hawass, PhD; Yehia Z. Gad, MD; Somaia Ismail, PhD; et al) It was found that he suffered from Kohler Disease, which can impair the ability to walk and may have caused swelling and pain in his foot. This is backed up by the numerous walking canes found in his tomb, which showed signs of use, although Professor Salima Ikram says the use of them was fairly light. He may have also suffered from familial epilepsy, which would have caused seizures.

An interesting hypothesis for Tut and his parents has been that they suffered from Marfan syndrome. This is a syndrome that can cause abnormally long limbs and fingers, slightly feminized appearance, a curved spine, and flat feet.

What’s so interesting is that the artistic style of the Amarna period actually backs this up – the busts and statues of Akhenaten, while being more lifelike than other eras of Egyptian art, are also slightly feminized. They show long limbs and androgynous features. For a long time, Egyptologists have speculated about whether these images reflected the truth or were just artistic license.

But after Akhenaten and Tut’s mummies were found, we got some answers. It was found that the pelvis of Akhenaten does not display feminine traits. Another feature of Marfan syndrome is dolichocephaly – a long, flat skull. But, none of the mummies tested exhibit that. Instead, they exhibit slight Brachycephaly, which is more of the elongated cone shape. The studies ruled that Marfan syndrome was not present.

It seems clear from current scholarship that the style of the Amarna period is much more artistic than physical. Probably related to the religious reforms of Akhenaten, and not based on real observation.

Tut was found to have suffered from Malaria – in fact, more than one strain of Malaria. Before a cure was found in the 1900s, Malaria could be very fatal. He would have been really uncomfortable in his final days.

But Tut’s actual killer was more innocuous – his body shows evidence of a sudden leg fracture, possibly from a fall. The broken bone in his left foot had festered, and alongside the malaria, proved fatal to the 19-year old. This then contradicts the story that he was helpless and crippled – he must have at least been active enough in his final days to have gotten injured.

But then, in reliefs, Tut is sometimes shown sitting instead of standing for certain activities like Hunting. So it’s just hard to tell the severity of his conditions.

Unfortunately, there is a lot we may never truly know about Tut – his mummy was simply too damaged and his time in history too shrouded in mystery.

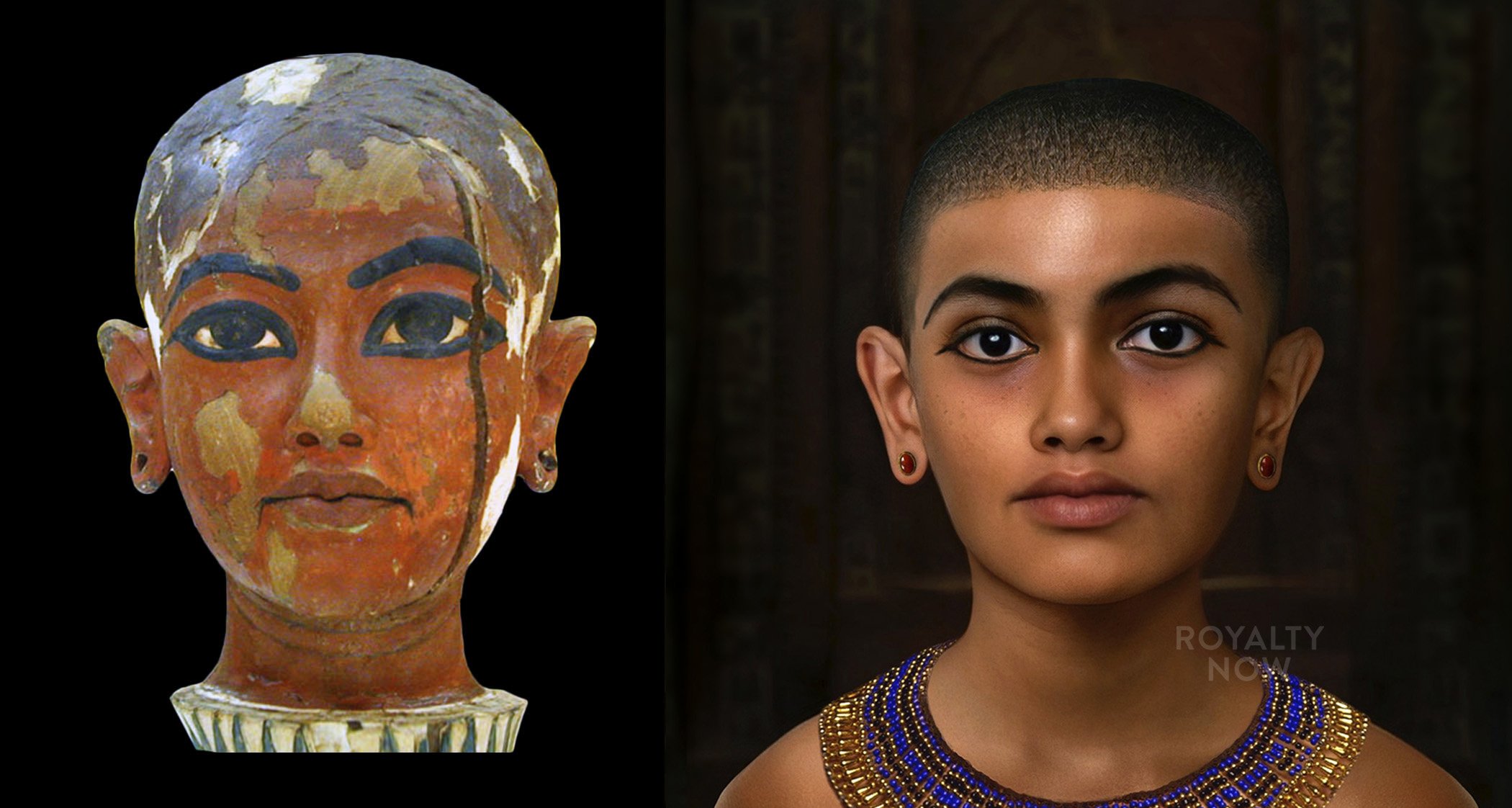

So, what do we know about how he would have looked in real life?

We know that he stood about 5’6”, and was fairly skinny. Professor Hutan Ashrafian says that he would have had an overbite with buckteeth, and been relatively frail. We know that at the time of burial, he had a shaved head.

Most scholars agree that the images of King Tut made by his own people, during his own lifetime, are what we should be looking towards for accuracy. Zahi Hawass thinks Tut’s burial mask is probably the best representation of him. It’s been noted that reconstructing directly from a mummy just isn’t reasonable or accurate, since mummy tissue shrinks by around 50%.

Professor Salima Ikram told LiveScience: “I think that he looked as he was represented, except that he had more of an overbite,”

We don’t have a ton of images of King Tut, just because of how short his reign was, but they all look remarkably consistent. I’m going to use his famous burial mask as well as the effigy of him found in the tomb as reference. This small effigy was made to represent him as a child, and it shows him emerging from a lotus flower, symbolizing regeneration.

We don’t know the exact skin tone or eye color of Tutankhamun. It’s been noted from his genome and skeleton that he can be considered North African. Now of course in the modern day, North Africans represent a huge range of skin tones and hair textures. I’ve tried to stick closely to what the sculpture represents, a tan reddish tone. Just know this is only one possibility.